Using internet search engines and any other resources, find at least 12 examples

of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century landscape paintings. List all of the

commonalities you can find across your examples. Consider the same sorts of things

as you did for the sketching exercise at the start of Part One. Where possible, try to find

out why the examples you found were painted (e.g. public or private commission).

Your research should provide you with some examples of the visual language and

conventions that were known to the early photographers.

Now try to find some examples of landscape photographs from any era that

conform to these conventions.

Collate your research and note down your reflections in your learning log.

This is where my distinct lack of knowledge of art history lets me down. I could only name three or four landscape painters prior to this exercise and even then I didn’t know which century they belonged to. I have been trawling the internet and my bookcase for inspiration, and found a catalogue/publication from a gallery which was useful (Hershkowitz et al., 2016), read the book A Picture of Britain by David Dimbleby (Dimbleby et al., 2005), and reread my log post on The Painting with Light exhibition that I saw in 2017 at Tate Britain (Farrow, 2017).

When I very first started this degree process, I asked myself the question if Turner and Gainsborough would have been photographers or remained painters if they had the technology available to them that is available now. The Painting with Light exhibition showed me that photography was important in terms of landscape painting quite early on. There are different types of ‘landscape’ photography and to some extent painting, these are: Seascape, urban, city, river, industrial, mountain, seasonal, forest and sky (or cloud) to the best of my knowledge.

In Dimbleby’s book (p10) he describes the influence on landscape painting of the French artist Claude Lorrain (1600 – 1682). There were strict rules on how the differing elements should be painted. A proper foreground, usually of dark overhanging trees, often with allegorical figures on green, the eye was then led to the middle distance, assisted by strategically placed rivers, bridges, hills or mountains. This has become known as a ‘classical landscape’ and although Lorrain lived in Rome, and painted the countryside around him, the subject of his paintings is not always as recognisable as the location! Dimbleby then goes on to describe William Gilpin’s (1724-1804) rules for the aspiring artist on how to compose a landscape painting or drawing (pp 18-19).

Faced with the confusion of scenery the artist should ensure that there are craggy mountains in the distance, not with smooth curved tops, but jagged. There should be a lake in the middle distance and the foreground should contain trees, rocks and cascades of water. he was very particular about the colour of the rocks. Grey was preferable to red as it set off green foliage more effectively. Isolated buildings in the middle distance were also acceptable, but only if they were partially in ruins. Animals too had to be carefully selected and arranged to ensure a perfect composition. Preferring cows to horses and make sure not to put in too many. Three is the ideal number. Sheep are always acceptable as long as they haven’t been recently shorn.

These are perhaps things to consider when considering the paintings below.

18th Century Landscape Painters

Richard Wilson ( 1714 – 1782). “Lyn-y-Cau – Cader Idris” (Wilson, 1774)(I climbed this on a school trip, and was terrified. The painting brings the ridge back to me so vividly.) This painting has tourists wandering on the ridge, as well as a painter sketching/painting and yet another looking through his Claude glass. They seem to be arranged in a triangular style. It seems quite tranquil and yet the mountain has a menacing tone to it.

“Lyn-y-Cau – Cader Idris” Richard Wilson c.1774 Tate Archive CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

Whilst most people think of Ansel Adams when it comes to imposing landscape pictures, I also learned of an Italian photographer of mountains, when I was researching this subject. He is Vittorio Sella (1859 – 1943), and his photographs have become important not only in terms of photography, but also in terms of geographical history. Using photographic plates (which were not lightweight) he took images which showed those who couldn’t climb the mountains the sights that could be seen. The image below shows a foreground of ice caves, a middle distance of ice sheets and a far distance of craggy mountain tops. There are people visible in this image (bottom right) and they provide a valuable sense of scale, the cloud level is low, and the snow provides a sharp contrast to the dark rocky mountain tops.

Ice caves on the Aletsch Glacier, Alps, photograph by Vittorio Sella, silver gelatin print, 1884 (Fondazione Sella, Biella, via telegraph.co.uk)

Thomas Girtin ( 1775 – 1802). “Rue st Denis in Paris”

La Rue St Denis 1802 Thomas Girtin 1775-1802 Presented by the Art Fund (Herbert Powell Bequest) 1967 Tate Archive CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

This painting reminded me immediately of Eugene Atget’s photographs of Paris. In particular this one. The same perspective range, although not the same vista, but both stretch into the far distance and get us to use our imagination to ponder what is beyond our sight. An early ‘cityscape’ so to speak. Plenty of people in the painting, most of whom seem to be facing in the direction of the artist, while the hay wagon is going away from him. There is a lot to look at in this image, and yet in the photograph there is not a soul to be seen, the mood is dark and damp, almost foggy and threatening, as if a thriller is to be filmed here.

Rue De La Montagne Sainte Genevieve Eugene Atget/CCO

Jean-Honore Fragonard (1732 – 1806) “A Game of Horse and Rider”

A Game of Horse and Rider Jean Honore Fragonard C 1775/1780 National Gallery of Art

This painting is one of a series of people at play, and little is known about its original destination. However, I am drawn to the portrait format rather than landscape, and the tall trees framing the view. The Silver birches appear to be in full leaf and yet the tree that is forming the leaning post for the game is older and has more character, yet less leaves. There appears to be a gondola style boat with passengers in the middle distance, which seems to suggest that some sort of rules are being followed in the structure of the painting – Gilpin or Lorrain? More probably Lorrain given the date of the painting.

Giovanni Panini (1691 – 1765) “View of the Colosseum“

A View of the Colosseum of Rome Giovanni Paolo Panini c1747 The Walters Art Museum USA

This is a composite image really, and has theological and archeological elements added. In the foreground the urn and a tree, there are people scattered around the scene and green grass. The Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum both look very neat and tidy. Trees frame the sides of the painting and there are more buildings in the far distance. Not really a view that tourists of the time or certainly now would recognise. I think that is why I prefer photographic landscapes, although there is the personal edit of the landscape in choosing what ‘bit’ to photograph, and subject to a light hand in post processing, then the chances are that you will at least recognise the landscape you are viewing in it.

Giovanni Canaletto (1697 – 1768) “View of the Grand Canal Venice”.

View of the Grand Canal late 1720s Giovanni Antonio Canal (called Canaletto) Birmingham Museum of the Arts USA

Once again, a leading line of the canal takes the eye through the painting, the foreground is pinned by the gondolas, and the sides are framed by the buildings. People are present and shown in action rather than just standing still.

19th Century Landscape Painters

John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) “drainage mills in the fens”,

Drainage Mills in the Fens, Croyland, Lincolnshire circa 1830-1840 Photo credit Yale Centre for British Art

A dark painting, but the eye is drawn by the red coat or cloak the figure at the front of the painting is wearing. The mills are shown going into the distance, and the dark and moody sky with the light coming over the horizon hints at a storm passing through.

John Constable (1776 – 1837) “The View of Highgate from Hampstead Heath”,

The View of Highgate from Hampstead Heath John Constable C1834

Once again trees feature as a framing tool and to lead the eye, in the middle distance are buldings and in the far distance a church. Being unfamiliar with this view, I have no idea what the buildings are. It looks an idyllic part of the Heath. People are present in this painting

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) “the last of the buffalo” (reminiscent of Edward Curtis),

The Last Buffalo Albert Bierstadt 1888 National Gallery of the Arts USA

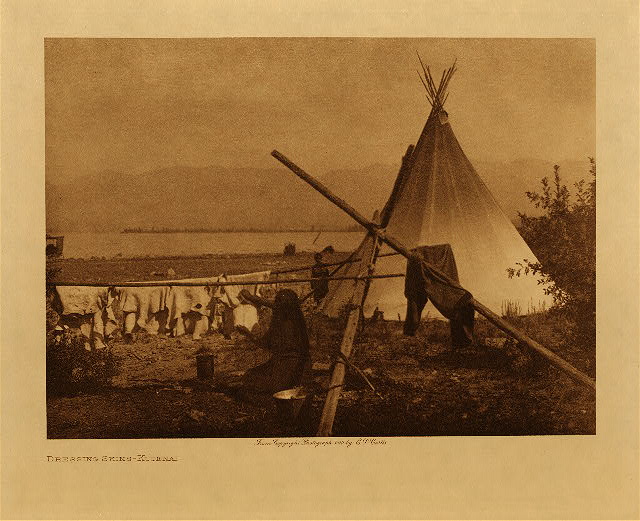

This painting reminds me of some of the images photographed by Edward Curtis, in his work trying to catalogue the vanishing nations of indigenous peoples in America. Although his images have turned out to be staged in many cases, for example those showing rituals and tribal dress, they do show a window into the lives of these peoples and how they have changed.

Dressing Skins – Kutenai © Edward Curtis 1910 Credit: Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003.

Before The Final Journey © Edward Curtis 1909 Credit:Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003.

In these two photographs you can see the mountains in the background, just as in the painting. Both photographs have a clear line in middle distance, and both images have a foreground object which is to one side.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840) “moonrise over the sea”,

Moonrise over the Sea 1822 Caspar Friedrich

A dark foreground of large rocks, slightly reddish brown in colour lead the eye towards the middle ground which has a group of three people, two women and a man. The far distance is the horizon line and yet the sails in the closer ship seem out of place. The moon is the bright spot in the painting and is coloured yellowish rather than white as we would possibly expect. Although the far ship still has all its sails up the nearer one is possibly beginning to bring sail in, perhaps they are approaching a harbour on the tide and the women in the painting are waiting for their sailors to return. This image asks questions and we don’t get any answers. The eye is drawn in a diagonal line from the bottom right hand corner to the top left hand corner.

Samuel Scott (1702 – 1772) “the Thames at twickenham”,

The Thames at Twickenham 1755-1765 by Samuel Scott

This painting is different in that it is framed to one side by buildings rather than trees, there is a small boat in the foreground and a pair of swans, but these are balanced by the larger boat on the left hand side more to the middle distance. The far distance is more buildings and trees but the sky and clouds take up a high proportion of the painting. The scene is peaceful rather than the more busy pictures painted of working quaysides and industrialised docks.

Isaac Levitan (1860 -1900) “Golden Autumn”

Golden Autumn 1895 Isaac Levitan

This painting is framed by trees at the side and has the river which draws the eye to the far distance, however there are no mountains just more trees. The colour is the main thing in this painting and makes me think of the Golden Hour when the light changes.

Jean-Baptist-Camille Corot (1796 – 1875) “Arleux-du-Nord, the Drocourt Mill”,

Arleux du Nord the Drocourt Mill on the Sensee 1871 by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Carot

Again, this is framed by trees, has people in the foreground, middle distance and the far distance, has a group of three ducks, the eye is led by the river, the path and the trees on the right hand side, to the building at the end of the painting.

More Landscape Photographs

Entrance to the park at Bradford by Faye Godwin © the british library board

While this photograph is presented in a landscape format to me it looks like it should be in portrait. The two concrete bollards in the foreground follow Gilpin’s thoughts that the rock should be grey, and it does show up the autumnal colours, the middle distance has the wheelbarrow and the man, and yet in this image the way the light brings out the colours in the leaves is just stunning.

Kenilworth Castle by Francis Bedford

This is similar to the Arleux du Nord painting, there is a river, and it is framed by trees with a building tucked away at the back higher up. The trees frame the photograph and the person is placed in the middle distance but is almost the last thing you see when looking at the image. The reflections are important and draw the eye towards her, after you have followed it up to the far distance and the castle.

These paintings and photographs have shown me that I need to consider composition very carefully when taking a landscape photograph and to consider all leading lines, framing of an image and if people are in the frame to consider whether to place them or to rely on people just passing through and hope to get them in the right place when I click the shutter.

References

Hershkowitz, R., Hershkowitz, kate, Gregory, T., Huxley-Parlour, G. and La Thangue, F. (2016). Seizing The Light: Photography In The Age of Invention. Beetles+Huxley.

Dimbleby, D., David Blayney Brown, Humphreys, R., Riding, C. and Tate Britain (2005). A picture of Britain. London: Tate Publ.

Farrow, H. (2017). Exhibition – Painting With Light. Three Lantern Photos – OCA Level 1 Expressing Your Vision My Learning Log. Available at: https://lanternphotos.com/2017/01/26/exhibition-painting-with-light/ [Accessed 20 Feb. 2020].

Tate (no date) Painting with light art and photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the modern age. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/painting-light (Accessed: 26 January 2017).